Car and gas prices are way up since the COVID-19 pandemic struck, and auto insurance and maintenance costs have been rising faster than inflation for years. The bottom line is that the cost of owning a vehicle is once again on the rise, reaching nearly $10,000 annually in 2021.

But for years before the pandemic struck, car buyers enjoyed mostly favorable conditions, including stagnant prices for new vehicles and low interest rates on auto loans, which had caused total operating costs to slide over the previous decade and a half. The question is whether the higher prices and interest rates we’ve seen in recent months will become the new normal.

Key Insights

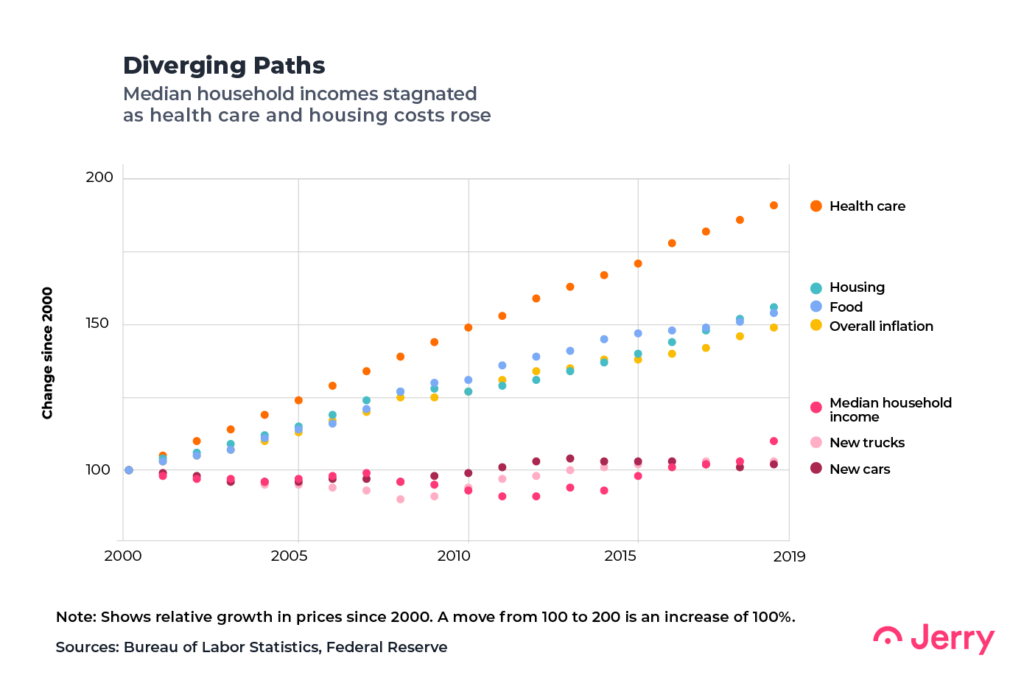

- Household incomes actually grew slightly faster than the prices of new and used cars and trucks from 2000 to 2020, according to data analysis by Jerry.

- Before the pandemic, new car prices had barely moved in two decades, rising only 2.3% from 2000 through 2019, well below the overall inflation rate, according to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). New car prices then jumped 18% higher from January 2020 through May 2022.

- Similarly, prices for new trucks rose only 3% from 2000 through 2019, before jumping 16% from January 2020 through May 2022.

- Prices for used cars and trucks fell 10% from 2000 through 2019, followed by a dizzying 50% increase from January 2020 through May 2022.

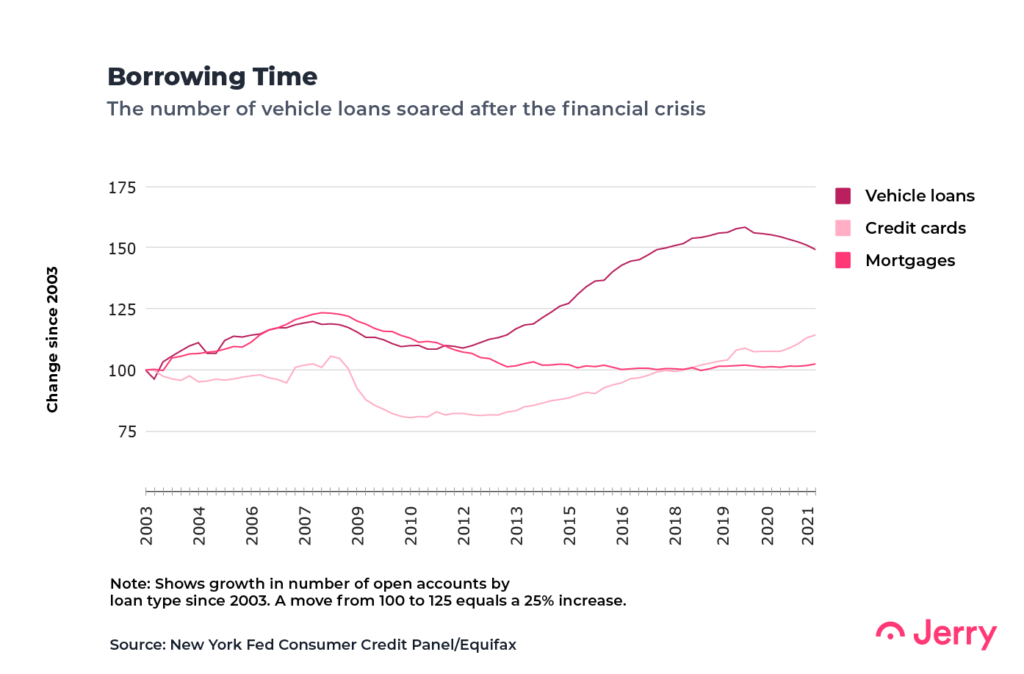

- Despite relatively modest price increases over the past 10 years, the number of new car loans has soared and their average value has risen nearly 50%, thanks partly to rock-bottom interest rates and longer repayment periods.

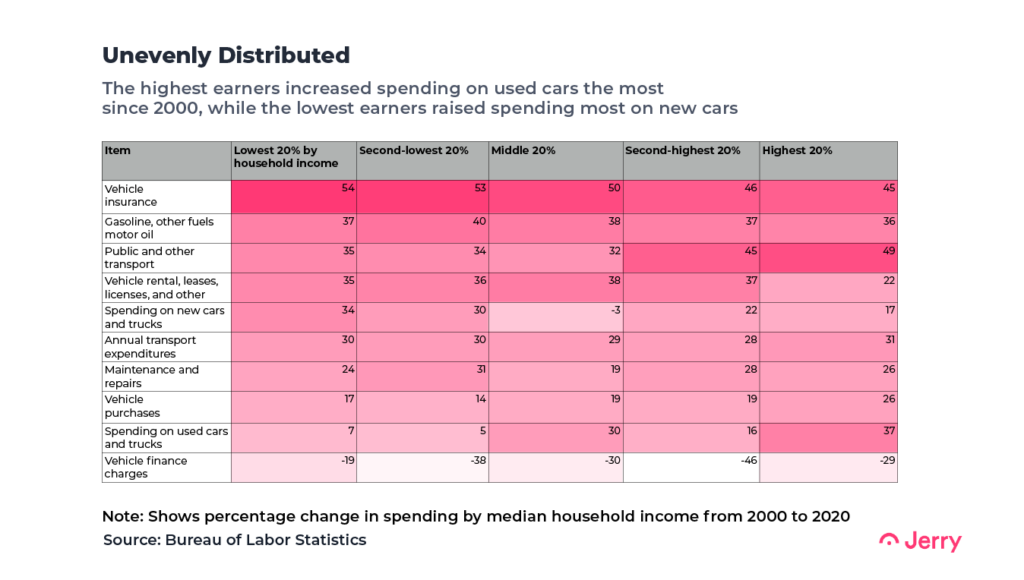

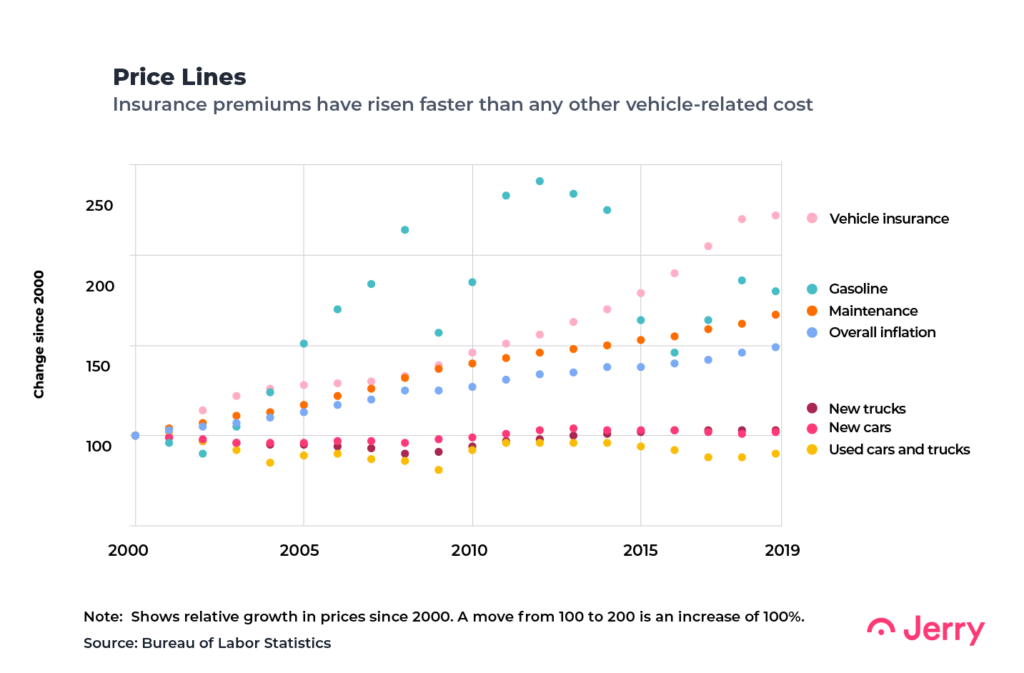

- Car insurance has been the fastest-rising vehicle ownership expense over the past two decades, followed by gasoline and maintenance and repairs.

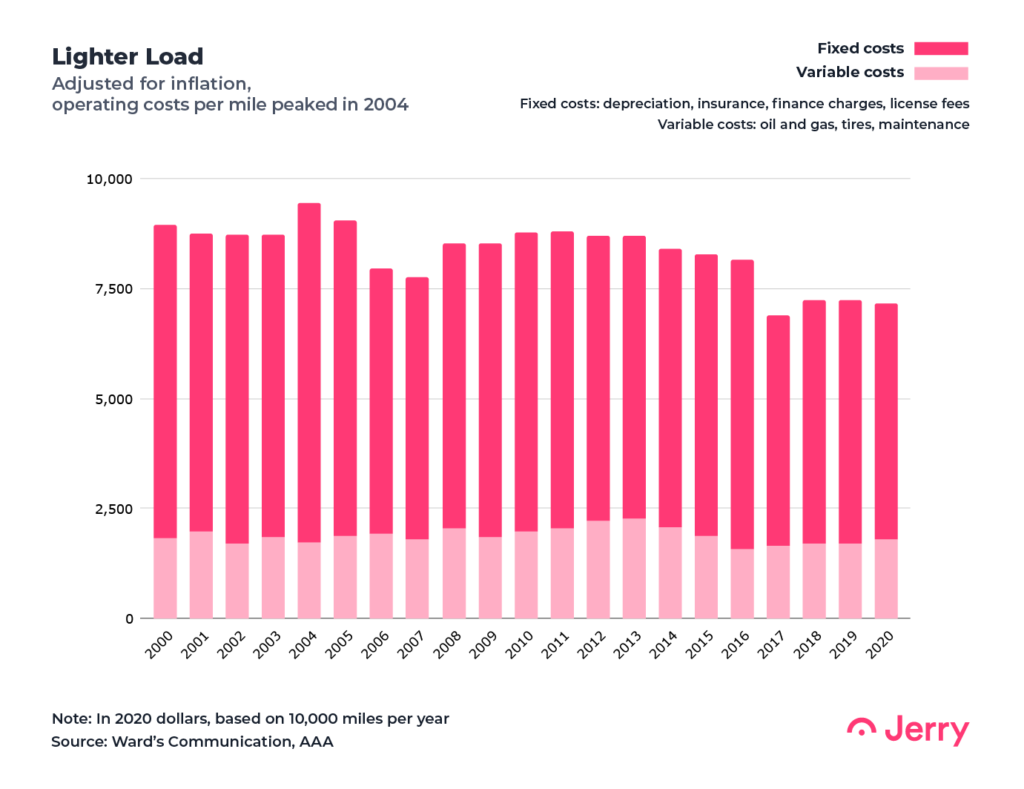

- Adjusted for inflation, annual automobile operating costs per mile peaked in 2004, according to data from Ward’s Communication and AAA.

Pandemic Woke Car Prices From Two-Decade Slumber

It’s been a painful couple of years for car buyers. The COVID-19 outbreak roiled the car market, driving the biggest price increases in years for new and used vehicles.

But it’s harder to complain when zooming out to a longer time frame. From 2000 through 2020, prices for new and used cars and trucks rose more slowly — and in some years fell faster — than household incomes. The problem was, those incomes lagged well behind housing and food costs and miles behind health care costs, meaning people still ended up with less money to buy that SUV or pickup they wanted.

Stretched households found some relief during those years from historically low interest rates, which kept monthly payments in check. But a new era of stronger inflation and higher interest rates could make it even more difficult for Americans to afford tomorrow’s vehicles.

Auto Lending Boom Masked Stress in Household Budgets

As more households struggled with their budgets in the wake of the financial crisis, tens of millions more people took out car loans, borrowing an ever greater amount. (Others held on to their old cars longer, pushing up the average age to a record 12.1 years in 2020.)

The number of vehicle-loan accounts in the U.S. increased by about half (45%) to 116 million from early 2011 to early 2020, growing faster than the numbers of mortgage and credit card accounts, according to Federal Reserve data. The size of those loans also ballooned, growing 49% over the past 10 years to an all-time high of $37,991 in 2022.

So why is the average loan up nearly 50% if new vehicle prices have been subdued? Extraordinarily low interest rates, particularly after the financial crisis, and the introduction of six- and even seven-year repayment periods have enabled people to keep monthly payments relatively low.

Those lower rates also explain why vehicle finance charges are the only category of transportation spending to decline across all income groups from 2000 to 2020, according to BLS data. All but one other category saw increases across the board.

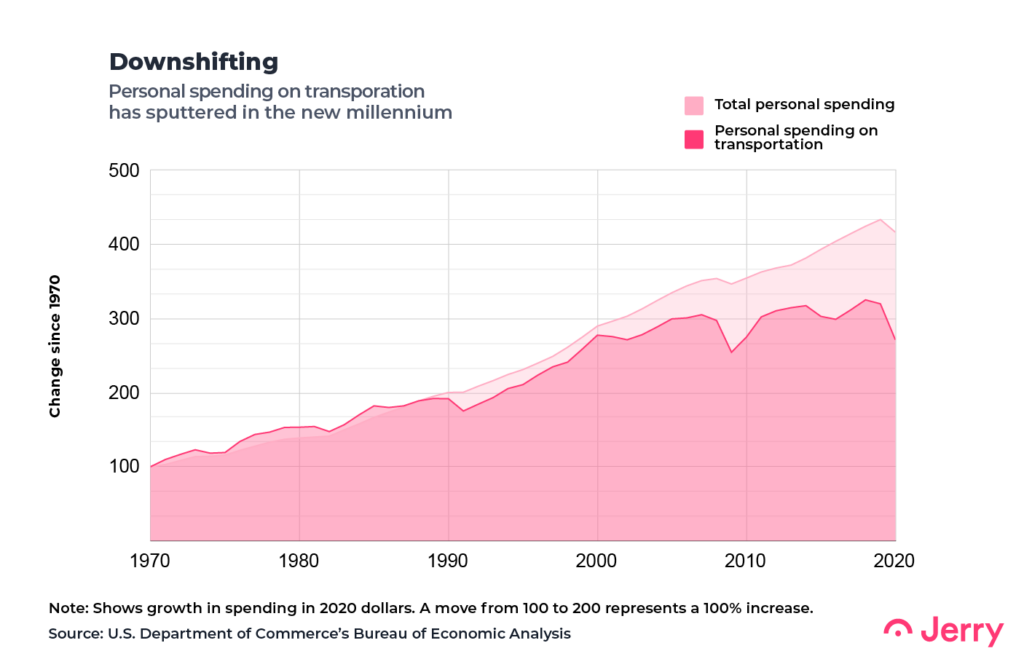

Even as many people borrowed more money to buy vehicles, their spending on transportation fell as a percentage of total personal spending, indicating that rising costs in other areas were eating up more of their paychecks.

Insurance Premiums Ranked as Fastest-Rising Expense

Some costs of vehicle ownership rose much faster than overall inflation. Insurance has been the worst, with premiums more than doubling from 2000 to 2020, followed by gasoline, and maintenance and repairs. All three outpaced inflation from 2000 to 2020.

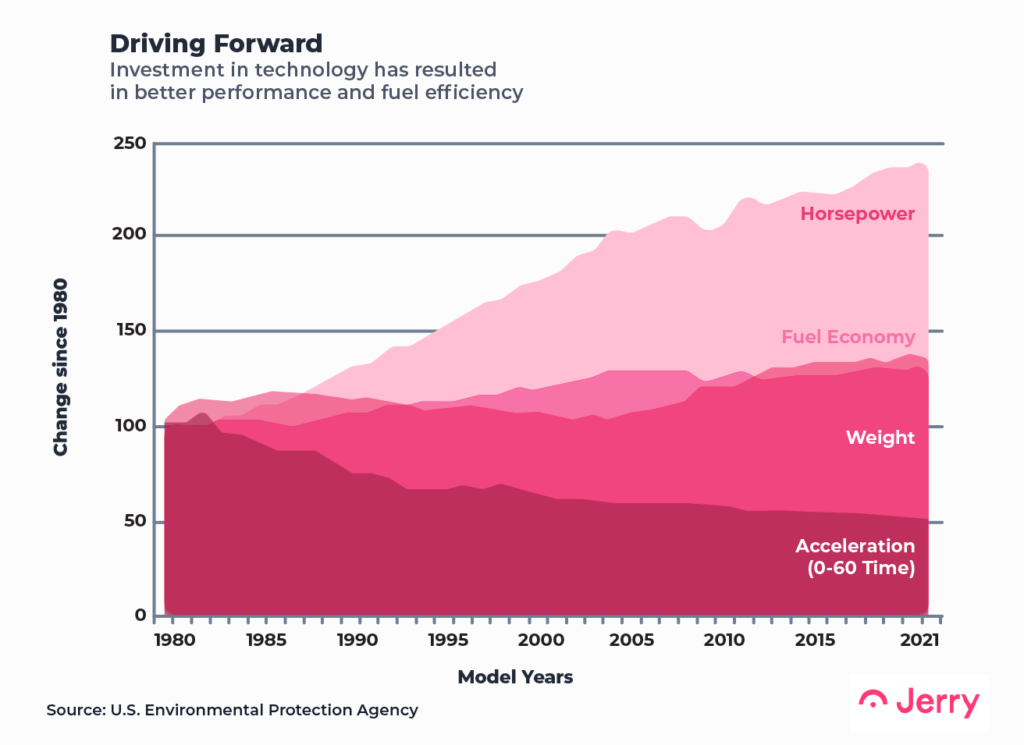

One reason insurance premiums have been rising so much is the increase in maintenance and repair costs, mostly due to the advanced technology in new vehicles. Today’s vehicles have dozens of computers running millions of lines of code and dozens of electronic sensors, with electronics accounting for about 40% of a new car’s price as of 2017, up from 18% in 2000. As of 2021, about 40% of new vehicles also come equipped with continuously variable transmissions, which improve efficiency and gas mileage. In 2000, zero vehicles were equipped with these advanced transmissions.

All that technology makes vehicles more expensive to keep up. But the good news is today’s cars, trucks and SUVs — though bigger and heavier — are quicker and more powerful, offer better fuel efficiency, produce fewer emissions, and include innovative safety features. This is an impressive achievement considering the relatively small increases in sticker prices over the longer term.

Those investments in advanced technologies also produced longer-lasting vehicles that depreciate more slowly than cars built 20 years ago. That’s one reason lenders are willing to stretch loan-repayment periods out to seven years: they are less worried about borrowers ending up “under water” with their loans.

Despite the gains in insurance, maintenance and gas prices, overall operating costs per mile, adjusted for inflation, peaked in 2004, and have mostly declined in recent years, thanks partly to lower finance charges and slower rates of depreciation. Still, the average annual cost to own a vehicle — assuming 15,000 miles a year of driving — reached nearly $10,000 in 2021, according to AAA.

Conclusion

Auto makers managed to keep car prices in line with household incomes, despite all the advanced technology in today’s vehicles. But steep increases in health care costs, housing prices, and food stretched household budgets all the same, leading record numbers of people to take out auto loans during the years when interest rates were at historic lows.

If overall inflation remains a problem, bringing higher vehicle prices and prolonged higher interest rates, more and more people could struggle with car payments and ownership costs, particularly if incomes continue to lag behind inflation. Longer repayment periods will only go so far to keep monthly payments affordable.

Methodology

Jerry examined data on prices of new and used cars and trucks and household spending from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, spending data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, lending and income data from the Federal Reserve, vehicle-performance data from the Environmental Protection Agency, and vehicle operating-cost data from Ward’s Communication and AAA.

Sola Nagaoki contributed to this study.

Henry Hoenig previously worked as an economics editor for Bloomberg News and a senior news editor for The Wall Street Journal. His data journalism at Jerry has been featured in outlets including CBS News, Yahoo! Finance, FOX Business, Business Insider, Bankrate, The Motley Fool, AutoWeek, Money.com and more.