Borrowers with poor credit ratings are paying more money on auto loans every month than those with good credit, posing a risk to their financial and economic prospects and the U.S. economy as serious delinquencies on car loans have hit a long-term high.

The fact that those borrowers pay more than everybody else reflects the financial peril that people with less money and poor credit must face when a reliable car is an absolute requirement to participate in American economic life, especially during a growing crisis of affordability in car ownership.

If defaults spiral upward, the pain could spread beyond their family finances. There are $1.6 trillion in outstanding auto loans in the U.S., and the risk of a recession over the next 12 months remains elevated. By value, nearly a fifth of all new car loans taken out over the past five years went to borrowers with credit ratings under 620, a level just above one commonly used threshold dividing prime and subprime credit ratings.

Key Insights

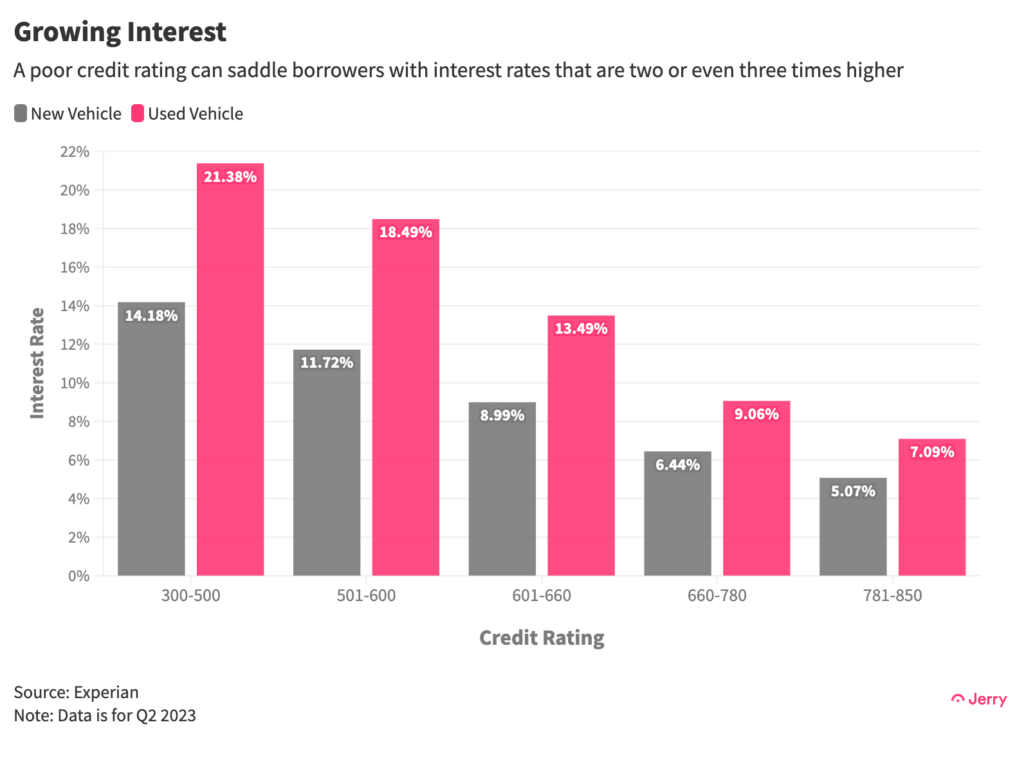

- A poor credit rating—subprime or deep subprime—can force a borrower to pay interest rates on auto loans that are two to three times higher than someone with good or excellent credit. Nearly a third of Americans have a subprime credit score.

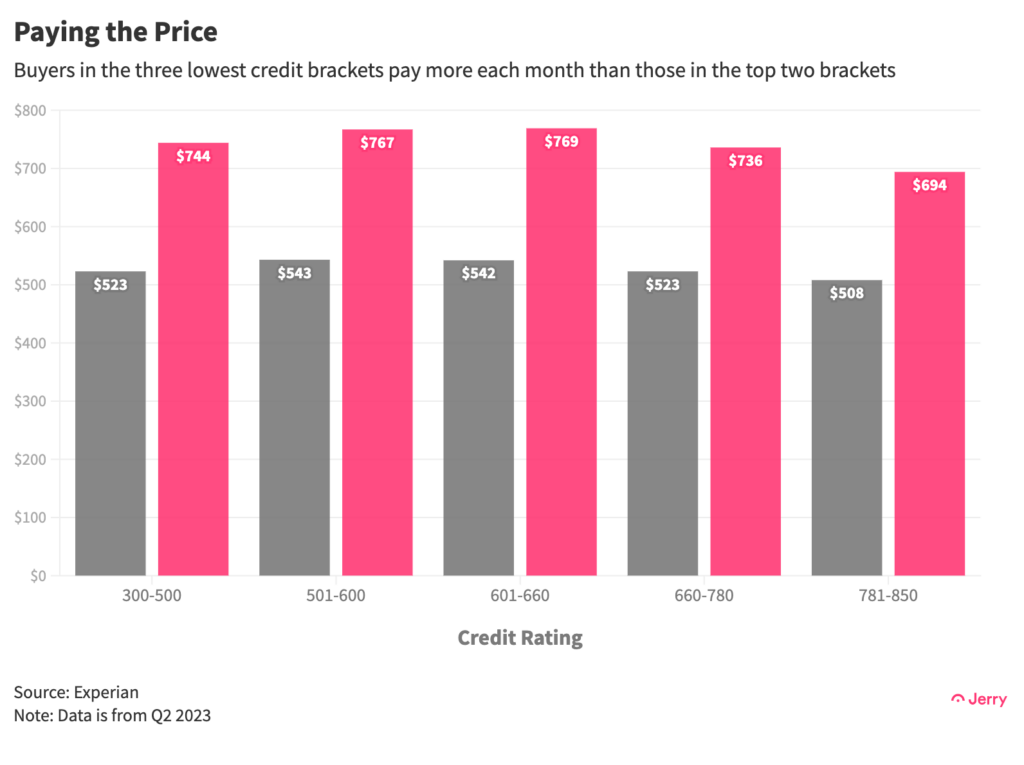

- On average, buyers with subprime and deep subprime credit ratings faced a higher monthly payment than borrowers with prime and super prime credit ratings in the April-June quarter of this year, the last for which data was available.

- Jerry analyzed a $26,000, 5 year auto loan for a 2015 Honda Accord. A borrower with a deep subprime credit rating would end up paying $11,580 more than a borrower with excellent credit, or nearly half (45%) the value of the vehicle. A borrower with subprime credit would pay $7,620 more, or about 29% of the value of the vehicle.

- The percentage of auto loans that became seriously delinquent (90+ days past due) in the past quarter (2Q 2023) hit 2.4% of the outstanding total balance, the highest level since 2010, the immediate aftermath of the global financial crisis. The delinquencies are concentrated among people with subprime credit ratings.

- The U.S. Federal Reserve found in a survey in June that the rejection rate for auto loans had reached 14%, double the rate five years earlier and the highest in at least a decade, as lenders try to stave off a potential crisis.

Paying a Premium

But the rates can vary dramatically and the consequences can be hugely burdensome.

Generally, buyers in the lowest credit bracket—deep subprime—suffer interest rates that are about three times what someone in the highest bracket would face, while buyers in the subprime bracket must accept rates that are roughly twice as high.

That makes a big difference over time. If both took out a $26,000 loan for 60 months to buy a 2015 Honda Accord, for example, the buyer with a deep subprime credit rating would end up paying $11,580 more than the buyer with excellent credit, if both paid off the loan in five years. That’s equal to nearly half (45%) the value of the vehicle.

For a buyer with merely subprime credit instead of deep subprime, the difference is still onerous: $7,620 more, or about 29% of the value of the vehicle.

For the most part people with good and poor credit aren’t buying the same vehicles. But the difference in rates is powerful enough that on average borrowers with the lowest credit scores still face higher monthly payments than those with the highest credit scores.

Of course, it’s commonly accepted practice to charge higher interest rates for people, companies or countries who pose a higher risk of not repaying their debts. It’s how lending markets work—and it makes sense, as far as that goes.

But it’s not quite as simple as that when it comes to the auto loan market. For one thing, the market is less regulated than mortgage lending, for example, and is rife with abuse, including higher markups on vehicles and loans when the buyer has a subprime credit rating. A study by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, a U.S. government agency, found that the highest interest rates charged for borrowers with subprime credit weren’t entirely justified by the actual risk of default.

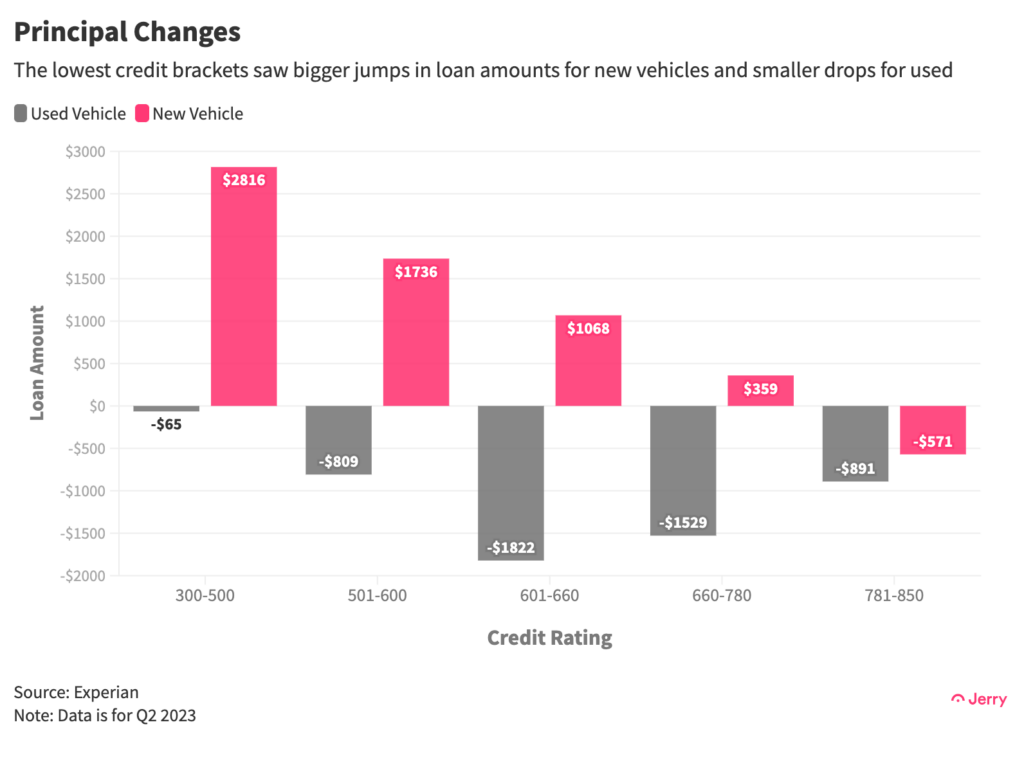

The CFPB also found that people with deep subprime scores may have a limited ability to simply buy cheaper vehicles, likely because dealers, particularly buy-here, pay-here dealers, only make certain vehicles available and at certain prices. It noted that the median value of vehicle prices paid by people with prime credit scores rose 30% from 2019 through mid-2022, while the median value rose about 60% for people with deep subprime credit ratings.

A look at changes in average loan amounts over the past year reveals an imbalance as well. The data shows that price changes of new and used vehicles between the second quarter of 2022 through the second quarter of this year aren’t reflected in the loan amounts taken out by people with poor credit scores. They saw the biggest increase in loan values for new vehicles, and the smallest declines in loan values for used ones.

Another possible explanation for this is that borrowers with subprime credit ratings aren’t in a position to negotiate or walk away, whether due to having insufficient information about their option or a lack of leverage. They know they need a car and they’ll need a loan to get one.

Rising Delinquencies

While delinquencies and defaults have hit the highest level in more than a decade, and are concentrated among people with subprime credit ratings, so far we’ve avoided the kind of crisis

The share of overall auto loans held by buyers with poor credit scores has fallen in recent years, from 21% in 2018 to 17% in the second quarter of this year, as banks and other lenders tightened requirements after delinquencies and defaults began to surge prior to the COVID-19 outbreak.

That tightening marked a reversal from the aftermath of the Great Recession, when lenders were eager to offer auto loans to just about anyone after default rates on auto loans during the financial crisis came in much lower than those on houses and credit cards. (That is one indicator, if one is needed, of how essential cars are to daily life in the U.S.) The banks were eager to lend because loans to people with subprime credit ratings are highly profitable.

Conclusion

In a country where car ownership is a basic need, saddling the most financially precarious borrowers with the steepest payments doesn’t make a whole lot of sense if your goal is accessible car ownership and a thriving economy. Those payments themselves are no doubt contributing to delinquencies and defaults, and in many cases perpetuating a cycle of poverty, which often begins with medical debt.

A Federal Reserve study found that people who lived in zip codes with higher percentages of subprime credit ratings were more likely to be non-White, have lower levels of educational and workplace achievement, less likely to have credit cards and mortgages but similar levels of student loan and auto loan debt. It concluded that “the creditworthiness of households is intertwined with economic adversity at the neighborhood level.”

Methodology

Data on different interest rates, monthly payments and loan amounts for different credit brackets was drawn from Experian and was for the second quarter of 2023. Data on auto loan delinquencies, rejection rates, and the percentage of loans made to subprime borrowers comes from the Federal Reserve.

The different lifetime payment amounts for a $26,000 loan were calculated using the average interest rates for deep subprime, prime and super prime borrowers.

Henry Hoenig previously worked as an economics editor for Bloomberg News and a senior news editor for The Wall Street Journal. His data journalism at Jerry has been featured in outlets including CBS News, Yahoo! Finance, FOX Business, Business Insider, Bankrate, The Motley Fool, AutoWeek, Money.com and more.