The “pink tax” is a well-documented phenomenon. It refers to the higher prices women pay for some goods and services compared to men, particularly for personal care items such as deodorants and fragrances.

But does that extend to car-ownership expenses such as vehicle prices, insurance premiums and repair costs? For Women’s History Month, we tried to answer this question. What we found is, it’s complicated. With products and services not generally targeted at specific genders, such as vehicles and car insurance, evidence of a pink tax is considered “limited.”

But there is evidence. Jerry found that certain young women pay more than men in the same age group for car insurance. We also called auto repair shops across the country and found that women were quoted slightly higher prices for a certain repair than men. And other studies have shown that older women pay higher prices at dealerships than men of the same age, and that dealers mark up interest rates on third-party car loans for women more than for men.

Key Insights

- Women aged 25-34 pay more than men in the same age group for auto insurance when both meet certain demographic conditions, including education, homeowner status and area of residence.

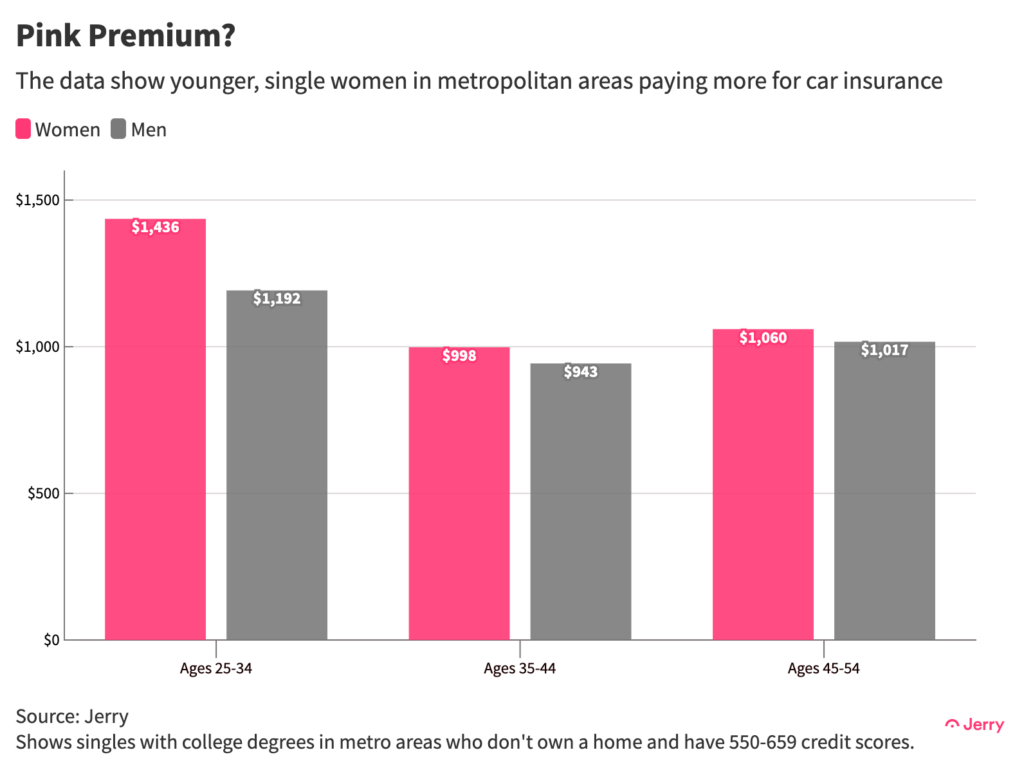

- College-educated, single women aged 25-54 who live in metropolitan areas, don’t own a home and have a credit score of 550-659 pay more for car insurance than men with the same profile. The price gaps for various age groups ranged from $43 (4.2%) to $244 (20%) a year.

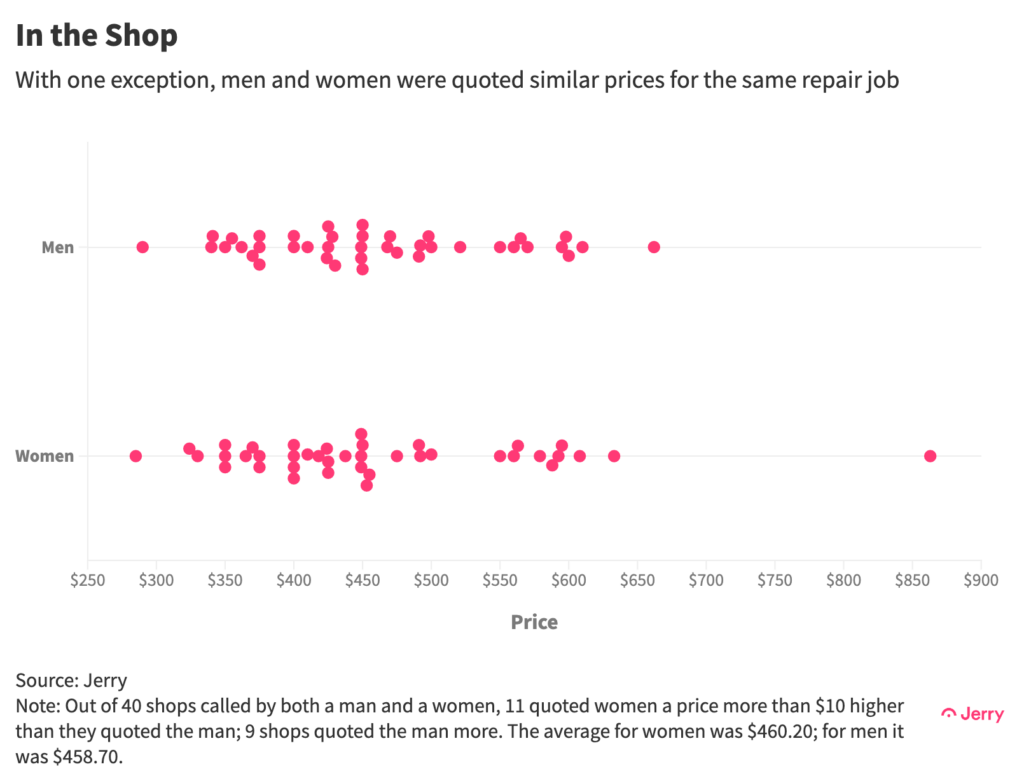

- In a small, non-scientific survey conducted by Jerry, repair shops in cities across the U.S. quoted women a higher price ($460.20) than men ($458.70) when asked about replacing front brake pads and rotors on a 2019 Toyota RAV4.

Premium Prices

A straight comparison of car insurance premiums for men and women, regardless of age or any other factor, found that men paid 7.8% more than women ($1,314 vs. $1,218) for basic liability insurance.

When looking only at drivers with clean driving records — no accidents or moving violations — men still paid 7.5% more than women ($1,218 vs. $1,133). In fact, men pay more than women in every age group when looking only at drivers with clean driving records and no other demographic factors. So it’s not just the high premiums for teenage boys skewing the results.

When Women Pay More for Insurance

But insurers consider many factors when setting premiums, including where you live, your marital status, whether you own your home, your credit score and education. So we created profiles that included all of those criteria and compared premiums. We focused on people with clean driving records who were living in metropolitan areas, and chose to compare prices for basic liability insurance to minimize any differences due to coverage levels and vehicle values.

To begin with, we compared prices for women and men using one demographic variable. We found that women aged 25-64 pay more than men in the same age groups if they are homeowners or live in an urban or suburban area. The difference in the homeowner category was as high as $74 a year, or 8.2%.

Then we created multiple profiles to see if either gender was consistently paying more. Looking at single people who hold bachelor’s degrees, live in metropolitan areas, are not homeowners and have a credit score of 550-659, we found that women pay $43 to $244 (4.2%-20%) a year more than men. The biggest difference was in the 25-34 age group.

But simply changing one element of that profile — marital status — yields a different result. Men pay more across all age groups. Changes to other criteria such as homeowner status yielded mixed results: Women of certain ages paid more, while men of other age groups did.

So mark us down as unconvinced that women generally pay a pink tax on car insurance. Even where we found that women do pay more, the average gap was narrow enough that it could easily have been a result of random chance.

Repairing the Damage

We also conducted a little experiment to find out if women pay more than men at auto repair shops. We called 50 shops in markets around the country, both independent and chain outlets, and asked each how much it would cost to replace the front brake pads and rotors on a 2019 Toyota RAV4. Each shop was called once by a man and once by a woman.

We obtained 40 usable results. Eleven shops quoted the woman a price that was more than $10 higher than they quoted the man, while nine shops quoted the man the higher price. The average quote for women was $460.20, while men received an average price of $458.70.

Again, put us down as unconvinced. It’s clear that some shops were trying to price-gouge the women, but it’s also clear that others were doing the same to the men. And given the small sample size, the results could very easily have been the result of random chance. In fact, removing just one repair shop — the source of the highest quote for both the men and women — changes the results. In that case, the average quote for men was $454.82, while the average quote for women was $449.87.

Interest Rate Markups

Car dealerships charge women a higher interest rate than men when arranging indirect financing, which is when lenders provide financing to the dealer, which then provides that financing to the buyer. In the process, though, dealers often charge the buyers a higher interest rate than they are paying the lender. And women get higher rates than men, one study found.

The difference was negligible for the individual — $26 over a 5-year, $24,000 loan — but amounted to $41 million a year nationwide for dealers over a 12-year period. But in a sign of possible progress on the pink tax, this narrowed over time, totaling only $10.9 million in 2015, the last year examined. Also, a statistically significant difference in markups was only identified in 16 states, with dealers in South Dakota and Wyoming ranking the worst.

Markups were larger for women with lower education levels, older women and women who were not trading in a car.

Negotiating Vehicle Prices

Another study found that women over the age of 70 pay the highest prices for new cars, about $240 more than the lowest-paying consumers buying the same vehicle.

The study was from 2017 and it uses data that’s a bit stale (from 2002 to 2006). But it did look at 20% of vehicle transactions in the U.S. during those years, so it was comprehensive.

In explaining their findings, the study’s authors cited a reluctance to negotiate among older women, perhaps because of brand loyalty or insufficient pricing information. They concluded that systematic discrimination was an unlikely explanation.

In fact, it also found that younger women performed no worse, and possibly better, at negotiating the vehicle price than men the same age, indicating that younger women are more likely to negotiate than older women.

Conclusion

The issue of gender-based price discrimination is an important one. Much hard work has gone into investigating it with the purpose of eliminating it where it exists. But when it comes to car-ownership costs, evidence of a pink tax is underwhelming.

Methodology

In comparing insurance premiums, Jerry looked at more than 50,000 final price quotes for basic liability insurance, meaning state-mandated minimum coverage, for drivers with no accidents or moving violations on their records. In comparing prices, we chose to look at the median prices instead of the average to limit extreme quotes distorting results.

In determining residency in a city, suburban area or rural area, we converted postal zip codes using the Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes designations adopted by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service.

We chose to focus our insurance study on drivers who identified as male or female due to the limited number of drivers identifying as neither.

Henry Hoenig previously worked as an economics editor for Bloomberg News and a senior news editor for The Wall Street Journal. His data journalism at Jerry has been featured in outlets including CBS News, Yahoo! Finance, FOX Business, Business Insider, Bankrate, The Motley Fool, AutoWeek, Money.com and more.